By Jenna, Miili and Arttu

1. Introduction

The University of Oulu, just like many other Finnish universities, houses a large number of non-native students and faculty whose first language is not Finnish. This is reflected in the multilingual linguistic landscape all around the University, where most signs have been translated to English, and where most places have been given an English title. Our aim in this essay is to examine the linguistic landscape of the University of Oulu through signs and posters found all around the Linnanmaa Campus. Our analysis will focus on finding similar conventions for multilingualism in the linguistic landscape around the campus through multimodality and semiotics. For this, we photographed multiple posters which were selected randomly, mostly from various signboards, as long as they included a language other than just Finnish and grouped them into a few categories.

2. Background

The University of Oulu is an extremely familiar place to us as students; however, we have never approached it from this point of view, which made considering the linguistic landscape around campus quite exciting. The university environment has to cater to different audiences from staff and students to visitors with different linguistic backgrounds and knowledge. This means that alongside Finnish and English, other languages may be used in different situations depending on the context. The University of Oulu language policy names Finnish as the official administrative language of the university, however, the site states that as an international university “the University of Oulu promotes the parallel use of Finnish and English in all its affairs. The use of other languages is viewed as beneficial and encouraged” (University of Oulu, n.d., para 1). Additionally, the university site mentions that they have a responsibility to organize studies and research in and of Saami languages. We were interested in seeing how English and Finnish are used on campus and mainly discussing the motivations behind the use of English in the campus environment, since our class is focused on English in Finland. This means analyzing why English is used and in which situations, which actions the signs perform and what kind of contextual or other knowledge is needed to decipher them.

3. Process

As our interest stemmed from our desire to understand more deeply the role of English within our own learning environment, we collected our data by casually taking pictures of signs around the university which utilized English. This included advertisements and posters on bulletin boards, as well as instructional signs. This way we could easily focus on analyzing the linguistic content and multimodality of the signs. There was no strict criterion for our data collecting other than the use of languages found on paper, which ended up being mostly posters. We excluded certain types of visible language phenomena from our data such as location signs/guide markers (TellUS, Foobar etc.) and university products (vending machines, laptop vendors, course books etc.) to limit our research. After the data was collected, we narrowed our focus to six signs we found most interesting and analyzed them, stressing on researching how the signs better communicate their intentions through the aid of the English language.

4. Materials

The study of linguistic landscapes is a fairly new research approach to understanding multilingualism, which considers the visual presence of languages in the public spaces in relation to ethnolinguistic vitality. In other words, it focuses on visual multilingualism that reflects linguistic identity within societies (Kelly-Holmes, 2014). The current research on linguistic landscapes focuses on language in relation to language policy, the spread of English, minority languages and multimodality (Gorter, 2013). Researching linguistic landscapes consist of the language of public road signs, adverts, street names, place names, and other public signs and altogether form the linguistic landscape of a territory or region, for instance (Abbas, Samad, Imam & Berowa, 2023).

Abbas et al. (2023) inspected the linguistic landscapes of a Southern Philippines university, gathering data from signs and banners, similar to our methods. They found that the majority of signs were monolingual, with only 9% being multilingual out of the data set of over 200 images. Interestingly, 85% were in English only, despite the linguistic diversity of the Philippines. The authors concluded that although English monolingualism was dominant on campus the findings do not generalize how multilingualism is practiced in the university of the Philippines, as linguistic landscapes can differ from the use of spoken language, for instance (Abbas et al., 2023). The same can perhaps be observed at the University of Oulu, where all the languages spoken on campus may not be visible on the linguistic landscape of the campus, with English and Finnish as the dominant languages.

In addition to portraying the possible inaccurate representation of language diversity within environments, the study of linguistic landscapes may depict and reveal the various language hierarchies within societies. English, which is a spreading global language, is often associated with modernity, luxury, and prestige (Piller, 2003), and is viewed within Finnish society as one of the top languages of the linguistic hierarchy. Thus, there are various motives for incorporating English within the landscape. Using motive analysis, a Japanese study identified three motives for utilizing English in public signages: 1) to attract the attention of the audience 2) to communicate societal rules and instructions better to foreigners, and 3) for the Japanese to become better accustomed to English (Rowland, 2015).

5. Analysis

The signages from our data collection can be categorized into three different types: 1) advertisements for university events, 2) advertisements for non-university affiliated social circles, and 3) instructional signs.

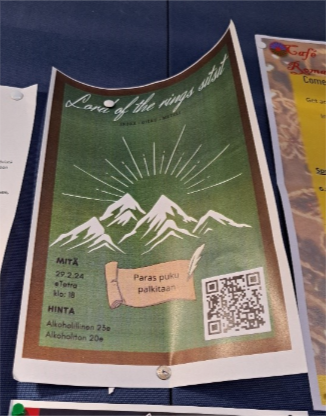

Figure 1: Poster for a student event

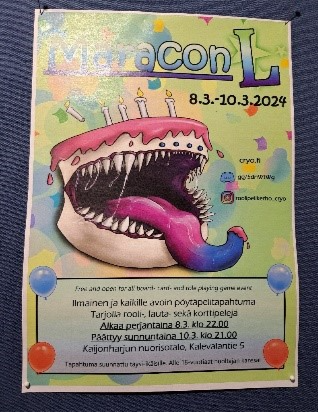

Figure 2: Poster for a CRYO event

The first poster (see Figure 1) is made by the student organizations Index, Gieku and Meteli. Interestingly, the poster’s title is “Lord of the rings sitsit”, even though the movie Lord of the Rings has a Finnish translation, Taru sormusten herrasta. The motivation behind the use of English may be to grab the reader’s attention and to cater to non-Finnish speaking audiences as well. However, the rest of the poster contains little information which is all in Finnish. Therefore, it is also possible that the organizations may have simply preferred how Lord of the rings sounds for the event name over its Finnish translation, and therefore they decided to use code-switching practices. The interpretation of the sign requires some contextual knowledge; for instance, knowing it is a movie and what the movie is about allows the readers to understand the theme of the event.

The same characteristics can be found in the second poster (see Figure 2), where English has been used to translate some of the Finnish text, but not all. This implies the event accommodates English speakers too through other multilingual participants, but the event’s main language is still Finnish. As these events are organized by independent clubs, it is possible they do not have the resources to coordinate a fully multilingual event.

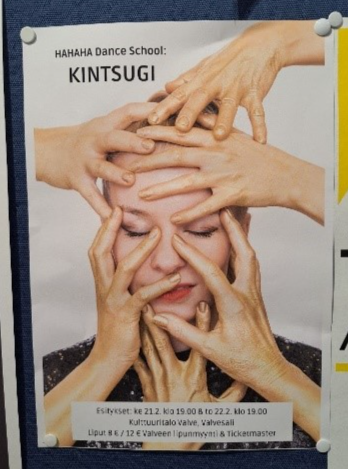

Figure 3: Hahaha Dance School ad

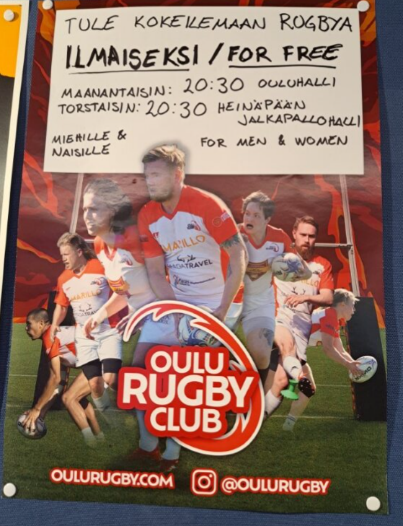

Figure 4: Oulu Rubgy Club ad

The following non-university affiliated advertisements were found on the same bulletin board at the university. The first poster (see Figure 3) by Hahaha Dance School incorporates Japanese, in addition to English and Finnish. All the relevant information about the show advertised show is in Finnish however. Consequently, the names of the show, Kintsugi, and for the dance school itself may have been chosen to grab the attention and bring out an interesting nuance that Finnish might not have to a native Finnish speaker.

As can be seen, the Oulu Rugby Club (see Figure 4) advertisement has combined both print and handwritten methods, utilizing mainly Finnish with a few English phrases incorporated. The relevant information concerning the rugby club has been handwritten within the designated white space at the top of the poster, perhaps indicating that the blank space can be reused. English phrases which have been utilized excluding the club’s title include “for free” and “for men & women”. The use of English here is similar to the Lord of the Rings poster, as it grabs the readers’ attention and communicates the bare minimum but most relevant information to foreigners.

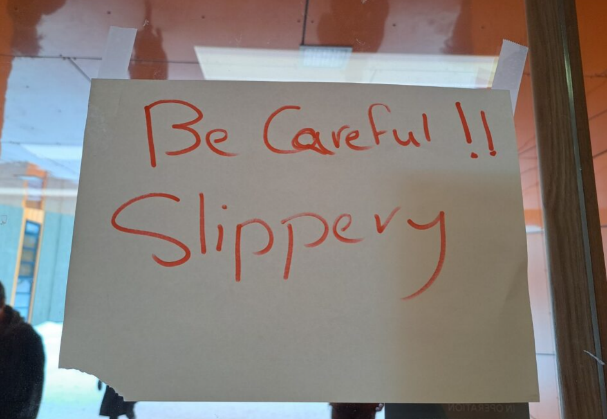

Figure 5: Handcrafted warning sign

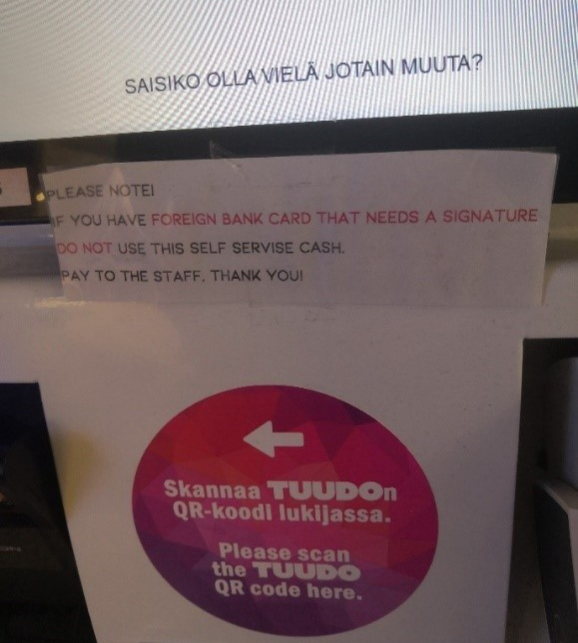

Figure 6: Instructions at a cafeteria

These signs (see Figures 5 and 6) are both informational and aim to direct the reader’s actions. However, there are differences in formality, and while one seems carefully prepared, the other seems as if it were crafted in a hurry. The former sign (Figure 5) uses as little wording as possible: “Be Careful!! Slippery”, to serve its purpose as a warning of icy ground. In relation to the multimodality of the sign, the red ink and large font further enforces the warning. However, it is clear the sign was hastily made as it seems to have been written on scrap paper and the handwriting is inconsistent. Why English was utilized could be for multiple reasons; however, the most likely reason is due to the involvement and consideration of non-Finns.

The sign on the right (Figure 6) includes two small signs at a self-service kiosk in a student cafeteria on campus, one of which is from the TUUDO company, and the other is made by cafeteria staff. The latter has likely been written by a non-native English speaker, considering there are small errors such as the incorrect spelling of “service”. The TUUDO text is in English and Finnish, as it targets anyone using the self-service kiosk. The smaller text on top is only in English, since it targets foreign students and staff with foreign payment cards. It is possible that there have been problems with foreign cards, which has prompted the staff to add the notion. Both English signs start with “please” and the longer text ends with a “thank you”. Interestingly, the TUUDO sign in Finnish does not include the word “kiitos” (“thank you” or “please” in Finnish), which showcases the different expectations around politeness and formality in each language.

6. Conclusion

The Linnanmaa campus hosts a wide variety of different demographics, which makes it a suitable place for a wide range of different advertisements. Our findings suggest that, within this data set, English is used to inform, grab attention, and to bring out a certain nuance to native Finnish speakers that Finnish might not convey, since not all posters which used English were explicitly targeted to non-native speakers. While our data set was small compared to the dozens of posters available, we think it offers a good glimpse of the overall linguistic landscape of today’s Linnanmaa campus.

Sources:

Abbas, J. H., Samad, B. M. A., Imam, M. H. M., & Berowa, A. M. C. (2023). Visuals to Ideologies: Exploring the Linguistic Landscapes of Mindanao State University Marawi Campus. Lingua cultura, 16(2), 187-192. https://doi.org/10.21512/lc.v16i2.8406

Gorter, D. (2013). Linguistic Landscape. In C.A. Chapelle (Eds.) The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (pp. 1 -5). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0719

Kelly-Holmes, H. (2014). Linguistic fetish: The sociolinguistics of visual multilingualism. In D. Machin (Eds.). Visual communication (pp. 135 – 152). De Gruyter Mouton.

Piller, I. (2003). Advertising as a Cite of Language Contact. In M. McGroarty (Eds.). Annual Review of Applied Linguistics: Language Contact and Change, 23(1), 170 – 183. Cambridge University Press.

Rowland, L. (2015). English in the Japanese linguistic landscape: a motive analysis. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 40 – 55. https://doi-org.pc124152.oulu.fi:9443/10.1080/01434632.2015.1029932

University of Oulu (n.d.). Language policy. https://www.oulu.fi/en/university/language-policy