Codeswitching, which according to Halmari and Cooper (1998) means “the mixing of two or more languages within the same conversational exchange and also within the same sentence”, is a common phenomenon especially in multilingual environments and among multilingual persons. In the globalized and multilingual world where more and more languages meet and merge, it is essential to observe codeswitching more thoroughly, as it has a wide range of sociolinguistic and rhetorical functions in human communication (Halmari & Cooper, 1998). On account of this, our project group decided to observe spoken interaction and codeswitching in casual everyday situations where codeswitching tends to emerge frequently. Moreover, we focused more precisely on how and when does English or another foreign language enter the original language of the discussion.

In this project report, we present the findings from the three observed interactional situations, and analyze the occurrence of codeswitching in those specific discussions. The small-scale research was conducted with the help of audio-recorded discussions and their transcriptions, which are also presented and used as examples in the analysis.

Dinner between a Spanish and a Finnish/French speaking person

In order to see the amount of use of the English language in spoken interaction, I analyzed a dinner conversation between a Venezuelan man and a Finnish-French woman. They both can speak Finnish well even though their mother tongues are Spanish and French and they know other languages as well. However, it is quite obvious that English is their second strongest language that they choose to use rather often during their conversation. From the transcript that was created based on their conversation one can identify a lot of code-switching as they are talking.

During the discussion, the man and the woman speak Finnish most of the time but one can see that there are specific reoccurring situations in which English is being used. For example, they use a lot of short exclamation phrases in English (oh really?, oh no!, whatever, fine, don’t worry, supposedly, excuse me?). These short phrases and words are being used as add-ons to their conversation and are spoken in English in order to emphazise their reaction and give it a more dramatic tone.

One can also identify loan words in their conversation. In most cases the loan words they use are finnishised, such as ”stalkata” and ”okei”.

These words are rooted in English but are transformed in a way that they appear to be Finnish words. A popular meme is also being quoted: ”Why you always lying?”.

Memes have recently become very popular in the midst of the young generation and it is rather normal for young people to send their friends memes as a way of communication. Certain memes have become so famous that they are being used not only in written but oral communication too. Most of the time they are quoted in English because most of the memes are created in English so that people worldwide may understand them.

What is interesting to note is that when one suddenly switches from Finnish to English, the other one also changes the language and continues the conversation in English.

However, there are a number of situations where they mix both languages. For example, they may start their sentence in English and say the rest in Finnish; ”Usually se oon minä joka puhun ja sinä kuuntelet”, ”I do the same, hyvää yötä sitten voi olla rauhassa”. This sudden language change in the middle of the sentence might be due to their forgetting the Finnish word equivalent.

It is obvious that a conversation between two multilingual people is bound to have a lot of code-switching. People who speak many languages tend to mix up languages in their mind and are more likely to forget words even though they actually know them. In this kind of situation, it can be easier for them to keep the conversation flowing by finding the word more rapidly in another language. In the end, it is clear that English has earned its place as the world’s lingua franca because even people who have other languages as their mother tongue find it natural to add English in their interaction. From this, we can only admit that the English language has quickly sneaked among at least the younger generation, and this is greatly due to social media.

Codeswitching in an English-German environment

The following abstract deals with the linguistic phenomenon of codeswitching in an English-German environment. Therefore, I recorded a dinner conversation with seven German native-speakers and one Dutch native-speaker, who understands and can speak a little bit German. The conversation was recorded in an English environment, since almost all of the speakers are in a semester abroad and used to speak in English in this environment.

With regard to Alexander Onysko (2012, 29) the use of English terms in the German language are “… dated back to the turn of the 20th century when Dunger drew attention to the rising occurrence of English terminology in German with his publications Wörterbuch von Verdeutschungen entbehrlicher Fremdwörter (‘Dictionary of Germanizations of Dispensable Foreign Words’, 1882; reprint in Dunger 1989) […]”. As one can see, the influence of English on the German language is not just coherent with the globalization but has started even beforehand. Furthermore, Onysko (2012, 3) points out that researchers have found out regional differences of the occurrence and use of Anglicism in Germany. The influence of English on the German speaking society is not in universal but shows differences between East and West and German-speaking countries like Austria.

In the conversation that I recorded, different kinds of codeswitching can be seen. According to Fricke and Kootstra (2016: 193 ff.) spontaneous codeswitching is done because of “[…] lexical boost effects, long-term priming effects, and stronger self-priming than interlocutor-priming”. The process of priming in this context “… typically refers to speakers’ tendency to re-use the syntactic structure of recently processed sentences. […] it appears to operate on many types of sentences and structures, […] and has played an important role in the study of the cognitive mechanism and representations that underlie language use (p. 181)”. Those codeswitches can be triggered by different words and situations. […] words, sharing representational overlap between languages (such as cognates) tend to increase the probability of a codeswitch, […] (p. 194). But as this research also points out: “… that words unambiguously belong to a single language tend to increase the activation of that language more than, e.g. cognates do, such a generalized triggering theory predicts that fully other-language words may in fact be stronger triggers than cognates (p. 194). This theory can be proved with the recorded conversation. In the following example the codeswitch happened, after one participant used an unambiguous German word:

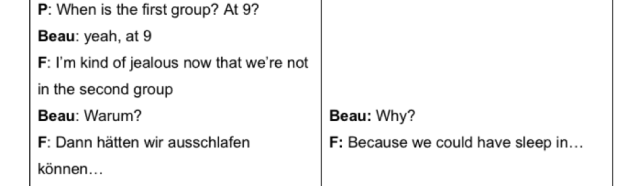

(Strohmer (2017): Transcript of the Dinner conversation)

(Strohmer (2017): Transcript of the Dinner conversation)

As it can be seen, the participant Beau asked in German and so did I answer in German and the whole conversation went on in this language. Again, in another part of the conversation the participant Beau was the trigger for the codeswitch:

(Strohmer (2017): Transcript of the Dinner conversation)

(Strohmer (2017): Transcript of the Dinner conversation)

In those examples, the purpose of codeswitching happened, because of the strong effort of self-priming. Even if the participant Beau is not a native speaker German, she tries to practice and keep up conversations in German. With this, she tries to be seen as a full German-speaking participant, even though she is not native, in order to get the feeling of belonging to the language discourse.

Codeswitching in Finnish spoken interaction

I constructed a small-scale research about the codeswitches me and my husband have produced. I come from a seemingly bilingual Finnish-Swedish background with a strong emphasis on Finnish and grew up in a city where the majority speaks Swedish. In addition, I’m fluent in English and quite fluent in German. My husband is from a quite monolingual Finnish background and has fluent English skills. The data is based on a dinner conversation and some other quotes from our spoken interaction, which I wrote down afterwards. As we were aware of the audio-recorded dinner conversation, the codeswitches were less frequent and we ended up speaking mostly English and switching quickly back to Finnish, for example when our two-year-old daughter grabbed the tortilla I was eating.

Codeswitching is usually seen as spontaneous, but consciously using a word from another language can also be considered as codeswitching. An example of this could be my use of [pansteiji], an adjective word from Swedish that is used for a ‘coffee that has stayed in the warm-kept pot so long that it has burn a bit and changed its flavour.’ I use it quite consciously, for there is no straight equivalent word in Finnish or one needs to produce a complete sentence to express it. Cost-efficiency and the search for the closest meaning are key concepts in codeswitching. Similar findings were proposed in Halmari and Cooper’s study “Patterns of English-Finnish codeswitching in Finland and in the United States”, where one of the subjects used “vitivalkoinen” in her spoken English, which means ‘white’ where “viti-“ is an intensifier that has not straight equivalent in English.

Switching to English in Finnish interaction can have other reasons, too. I switch to English whenever I need to say something to my husband that our daughter should not hear. For example, going to the shower is a topic we discuss only in English, for if she hears the word ‘suihku’ [shower], she immediately starts banging the bathroom door and undressing quite determinately. Therefore, to avoid this reaction and her upset if we are not going there immediately, we use English.

Another peculiar instance of codeswitching is that we both use English sentence starters in our Finnish interaction. My husband started a sentence with: “Speaking of työhuone..” [–the study] and continued with Finnish. Note that here, the borrowed words affect the Finnish noun. The Finnish equivalent ‘työhuoneesta puhuen’ might be harder to access from the brain at that moment and the English version is used but it changes the form of the noun. He did not produce *Speaking of työhuoneesta*, instead the noun ‘study’ gets its uninflected form in Finnish. To mention another example, I quite often use “Anyways” and then continue in Finnish. Here though, my pronunciation of the word is more Finnish-like, with the [w] closer to the Finnish [v]. One explanation of using the English starters is that Finnish doesn’t have a similar structure and the adverbials like “kuitenkin” [anyways] seldomly get the initial position in the sentence as in some cases it is considered ungrammatical. In both instances, the words implied a change of topic in some way, and the English structure would express it more efficiently.

Codeswitching happened also in an occasion, where a straight loan word changed the discourse to English. My husband told about a ‘déjà vu’ he was having, and I replied with “Like what?”. Here, the loan word that has been taken into Finnish without changing its form somehow tricked my brain to trigger the ‘let’s switch to English’-mechanism, though the word is a French loanword in English.

Conclusion

All the presented conversations proved how prevalent phenomenon codeswitching is in multilingual environments. In most of the cases, codeswitching seemed to occur spontaneously in diverse situations, for example, due to triggering words and expressions, which lead to switching the language of the whole discussion. In some of the situations, it occurred due to forgetting of the original language, and by replacing it with a prevalent other language, such as English, the commonly known lingua franca, which has a strong impact on language use through social media. In many occasions, the speakers also started their sentences in English, such as “Speaking of työhuone”, mixing together two sentence structures, e.g. for starting a new topic in discussion.

However, codeswitching can also be intentional and conscious, such as in the cases of not wanting someone to understand a specific word, or when one language does not have a total equivalent for conveying the desired message, and a word from another language is more precise and suitable. Also, codeswitching was used when the speaker was self-priming, and willing to learn a language in order to feel being part of a language discourse. Moreover, codeswitching was used for rhetorical means, adding emphasis and tone to certain intentions of speech, such as “Excuse me?” in the first conversation example.

All in all, codeswitching is a complex sociolinguistic phenomenon which occurs in multiple situations. It would be interesting to investigate further, how codeswitching affects speakers’ language skills, and thus their linguistic identities.

References

Fricke, M. and Kootstra, G. J. (2016). Primed codeswitching in spontaneous bilingual conversations, Journal of Memory and Language 91, pp. 181-201. Elsevier.

Günther, S., Konerding, K-P., Liebert, W-A., Roelcke, T. (2007). Linguistik – Impulse & Tendenzen: Onysko, Alexander: Anglicism in German. Borrowing, Lexical Productivity, and Written Codeswitching, pp. 1-8. Walter de Gruyter.

Halmari, H. and Cooper, R. (1998). Patterns of English-Finnish codeswitching in Finland and in the United States. Puolin toisin: suomalais-virolaista kielentutkimusta: AFinLAn vuosikirja 1998, pp. 85-99.